Why Haven’t Loan Officers Been Told These Facts?

Is an ABA Disclosure Required from Parties to a Marketing Services Agreement (MSA)?

In short, yes.

Many real estate professionals are confused about what constitutes an MSA or ABA. For example, the classic ABA involves two or more persons with shared beneficial ownership interests of a settlement service provider. But is a desk licensing arrangement an ABA?

ABAs are defined by the RESPA and Regulation Z. No such statutory or regulatory definitions exist for Marketing Services Agreements.

ABAs are not uncommon. For example, a lender and a builder form a mortgage company. Both persons put up capital. Both persons are entitled to a return on their investment. When the builder refers business to the ABA, they do not collect referral fees; they collect regular profit distributions according to their interest in the ABA. Like a dividend payment, when the ABA Business distributes profits or losses, the ABA business does so according to bonafide interests in the enterprise.

12 CFR §1024.15(b)(3)(i)(A). Bona fide dividends, and capital or equity distributions, related to ownership interest or franchise relationship, between entities in an affiliate relationship, are permissible.

Is an ABA an MSA or Vice Versa?

In the past, the CFPB took a dim view of MSAs. From then, Director Cordray’s infamous 2015-05 Compliance Bulletin:

MSAs often involve providers of settlement services in a mortgage loan transaction, such as a lender, real estate agent or broker, or a title company. They may also involve third parties who are not settlement services providers, such as membership organizations. MSAs are usually framed as payments for advertising or promotional services, but in some cases the payments are actually disguised compensation for referrals.

As mentioned earlier, RESPA and Regulation X do not expressly define MSA. However, the courts have provided some clarity. After the CFPB repeatedly got their butts kicked in several Section 8 adjudications, they rescinded their damning MSA Compliance Bulletin 2015-05, effective October 2020.

This was an opportunity for the CFPB to clarify ABAs and MSAs. Instead, the CFPB went back to the Section 8 drawing board and published a flaccid FAQ on 12 CFR § 1024.14(g)(1)(vi), gift-giving, and promotional activities. Alas, there is much confusion about MSA compliance.

Maybe that is the point. The regulator does not have to say “don’t do that.” They only need to create an air of uncertainty to deter most stakeholders from MSAs due to the risk of noncompliance.

ABA Defined by RESPA, Promulgated Under Regulation X 12 CFR 1024.15

The term “affiliated business arrangement” means an arrangement in which a person in a position to refer business, or AN ASSOCIATE of that person, has an AFFILIATE RELATIONSHIP with a SETTLEMENT SERVICE PROVIDER.

ABA refers to a relationship between two or more persons. Persons could be individuals or businesses.

If the referring party or the associate of the referring party has an affiliate relationship or direct beneficial ownership interest of more than 1 percent in a provider of settlement services, that is an ABA.

Regulation X Defines Affiliate Relationship

12 CFR §1024.15(c)(def2) “Affiliate relationship means the relationship among business entities where one entity has effective control over the other by virtue of a partnership or other agreement.”

An example of an affiliate relationship is an individual MLO and their sponsor or employer.

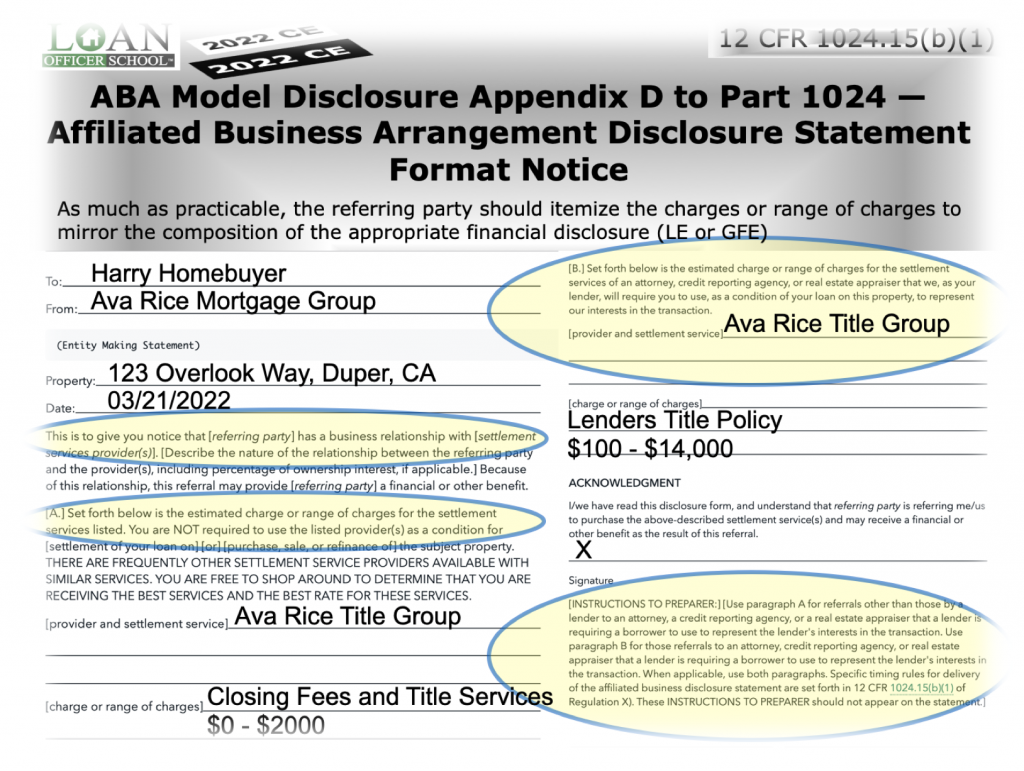

When a person refers a consumer to an affiliate or an associate affiliated with a service provider, the referring party must provide written disclosure describing the nature of the ABA to the consumer.

MSAs May Transcend ABAs, But Fit within 12 USC 2602 (8)

RESPA Defines Associate Relationships

For example, desk licensing could be an example of an MSA. A real estate broker maintains a desk licensing agreement with a mortgage broker when the broker accepts a fee from the mortgage broker for using space, furnishings, and fixtures in the real estate broker’s office.

Under RESPA, the mortgage broker is the “associate” of the real estate broker. Also, under RESPA, the mortgage broker has an “affiliate relationship” with their mortgage company. The mortgage broker may also have a direct or beneficial ownership interest of more than 1 percent in the mortgage company. When the real estate broker refers a consumer for a mortgage to the lender, the consumer must receive the ABA disclosure at the time of the referral.

12 USC 2602(8) . . . the term “associate” means one who has . . . a relationship(s) with a person in a position to refer settlement business.

Relationships fall under the rubric of an ABA. A spouse, parent, or child of the referring party is an associate. Additionally, RESPA describes specific relationships subject to the associate label.

12 USC 2602(8)(D) Anyone who has an agreement, arrangement, or understanding with a person in a position to refer settlement business, the purpose or substantial effect of such agreement, arrangement, or understanding is to enable the person in a position to refer settlement business to benefit financially from the referrals of such business.

MSAs are for building business with referral partners. Lenders enter into MSAs to get business from real estate agents and builders. When the lender compensates the counter-party for marketing services, that person benefits financially from the referrals received by the lender. If the lender does not get any referrals from the MSA, the lender abandons the MSA.

12 CFR 1024.14 (g)(iv) Regulation X states that RESPA permits “A payment to any person of a bona fide salary or compensation or other payment for goods or facilities actually furnished or for services actually performed.”

12 USC 2607(c) is where the CFPB had some interpretive difficulties.

12 USC 2607(c) Nothing in this section shall be construed as prohibiting . . . the payment to any person of a bona fide salary or compensation or other payment for goods or facilities actually furnished or for services actually performed.

The CFPB seems to get the letter of the statute right in Regulation X. However, according to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, the CFPB enforcement actions surrounding compliant payments within an MSA structure flunked law school 101. Ouch.

Nothing prohibits payments for services or goods, not even when referrals follow the MSA activities. The CFPB could not get their anti-kickback minds around the arrangement and square that a party to an MSA referred business to the counterparty without violating RESPA 8(c).

Referrals should not be a stumbling block to a compliant MSA!

Next week the Journal takes a look at executing the ABA disclosure.

Behind the Scenes

Do White Men Get Better Mortgage Pricing Than NonWhite Men and Women? The CFPB Identifies Patterns of Uneven Pricing Exceptions Along Protected Class Lines

ECOA prohibits a creditor from discriminating against any applicant regarding any aspect of a credit transaction based on race or sex.

In a recent report, CFPB examiners observed that mortgage lenders violated ECOA and Regulation B by discriminating against African American, and female borrowers. The examinations revealed that lenders grant pricing exceptions based upon competitive offers from other institutions more frequently to white men than women or African American applicants.

Price matching occurs when a lender grants a pricing concession based on the offer of a competitor.

The examination team identified lenders with statistically significant disparities for the incidence of pricing exceptions for African American and female applications compared to similarly situated non-Hispanic white and male borrowers.

The disparity appears to have roots in several areas. The CFPB report does not claim to have evidence of discriminatory treatment on the part of the lenders. The problem is the lenders can’t prove they don’t discriminate. Unlike the legal precept of innocent, until proven guilty, no such precept exists in civil matters such as ECOA compliance. If the covered person fails to provide the evidence sufficient to establish compliance on examination the lender will have problems.

The CFPB specifically commented on three problem areas.

- The failure of the lenders’ mortgage loan officers to follow the lenders’ policies and procedures concerning pricing exceptions

- The lenders’ lack of oversight and control over their mortgage loan officers’ use of such exceptions

- Managements’ failure to take appropriate corrective action surrounding self-identified risks

“The examination team observed that lenders maintained policies and procedures that permitted mortgage loan officers to provide pricing exceptions for consumers, including pricing exceptions for competitive offers, but did not specifically address the circumstances when a loan officer could provide pricing exceptions in response to competitive offers.”

That is sufficient evidence of a deficient Compliance Management System (CMS). No supervision, no management, and no accountability. The lender’s risk assessment (e.g., how and what can go wrong) and the overall CMS must reasonably prevent noncompliance and consumer harms.

“The lenders relied on managers to promulgate a verbal policy that a consumer must initiate or request a competitor price match exception. The examination team identified lenders with statistically significant disparities for the incidence of pricing exceptions for African American and female applications compared to similarly situated non-Hispanic white and male borrowers.”

“Examiners did not identify evidence explaining the disparities observed in the statistical analysis. Instead, examiners identified instances where lenders provided pricing exceptions for a competitive offer to white male borrowers with no evidence of customer initiation.”

“Furthermore, examiners noted that lenders failed to retain documentation to support pricing exceptions. Also, lenders’ fair lending monitoring reports and business line personnel raised fair lending concerns regarding the lack of documentation to support pricing exception decisions.”

The CFPB is saying that a more significant percentage of white males get pricing exceptions than non-white males and women. They don’t know why. But in the absence of evidence that the pricing exception was in response to a competitive offer, what are the examiners left to surmise?

Furthermore, when the exam reveals evidence that the lender’s internal audits cite the lack of pricing exception evidence and management does nothing to remedy the issue, that speaks volumes. Inattention to exceptions from internal audits communicates all the wrong things.

The lender could have the best intentions but appears to practice giving better terms to white men than non-white men and women for no apparent business reason.

This problem is somewhat simple. The lack of formality and process will get you every time. Verbal instructions for something as significant as pricing policy and fair lending compliance? If and when the lender desires to grant pricing exceptions, why not have the MLO complete an exception request? The lender then retains the exception request and evidence of the “competitive offer.” Heck, even an email chain with the prospective borrower is better than nothing.

The lender needs evidence that the exception originated with the applicant. Keep the records for a minimum of 25 months regardless of consummation or not. It might not be a bad idea to have the manager sign off on the exception and the business purpose evidence before granting the exception.

Consistency helps. Have a clear written policy on pricing exceptions. Implement procedures to ensure the policy is promulgated and followed.

Tip of the Week – Don’t Piss-Off Your Regulator

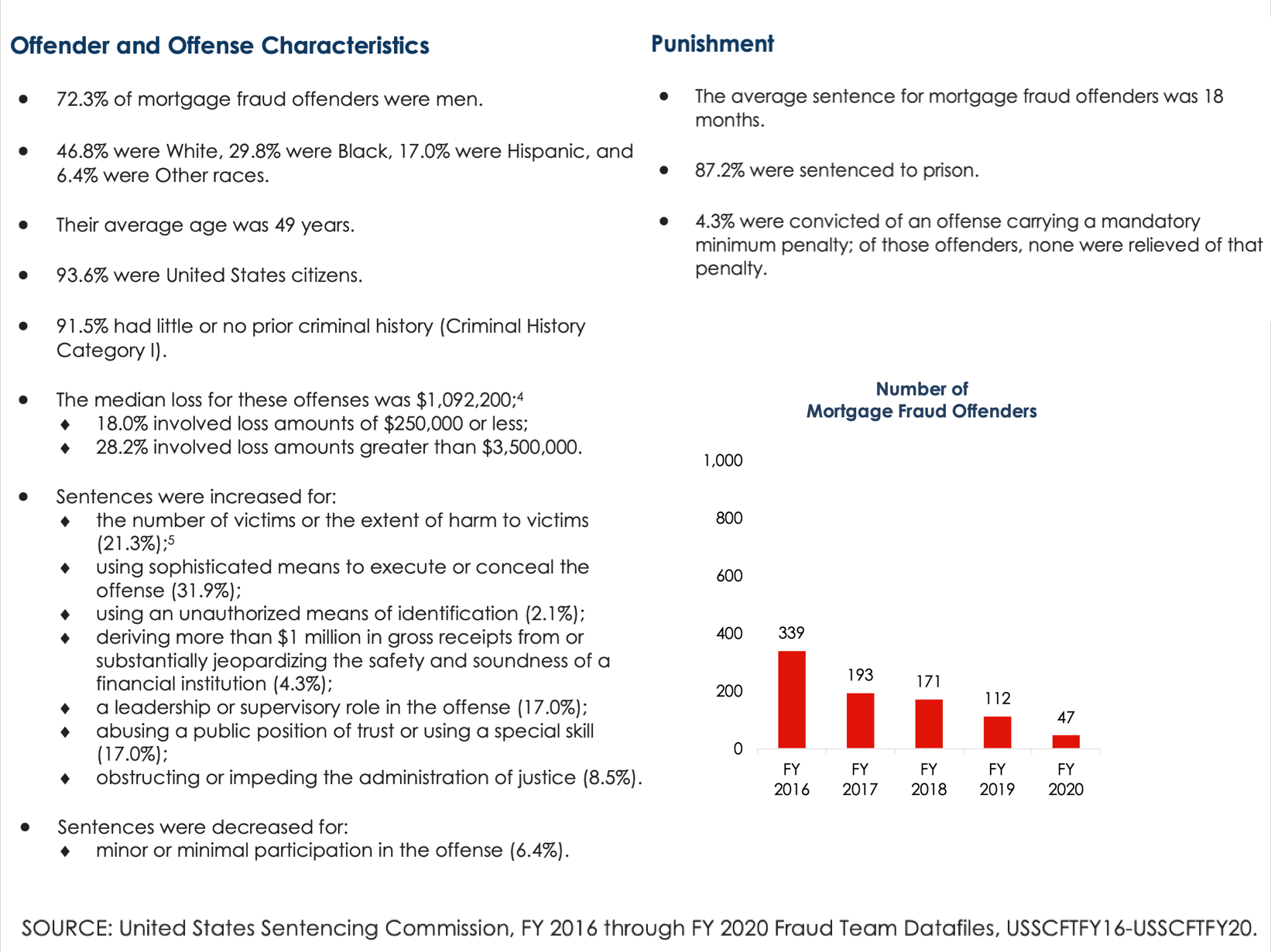

Hard Time for Mortgage Fraud Is Down, Sentencing By The Numbers

US Sentencing Commission releases data on mortgage fraud sentences through the most recently available period (2020)