President Barack Obama shakes hands with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi after signing the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act at the Ronald Reagan Building in Washington, D.C., July 21, 2010

Why Haven’t Loan Officers Been Told These Facts?

12 Years Later, Ongoing Title XIV Confusion

“I thought you could not base loan officer compensation based on loan type. For example, can I pay the loan officer a lower split on a bond program?”

The LoanOfficerSchool’s 2022 CE Course includes some ideas for implementing subprime lending policies. One such suggestion is that creditor-to-broker and broker-to-MLO loan agreements structure compensation so that subprime products earn lower profits than prime products.

In response to the lower profit on subprime loans suggestion, one of our valued customers fielded concerns regarding the Regulation Z prohibitions against paying originators based on the terms of the loan.

First, in response to the student’s question concerning paying lesser MLO compensation based on loan terms or programs, that is a noncompliant practice.

Disincentivizing the MLO from presenting the best solution is specifically what the Regulation Z MLO compensation rules are intended to curtail. Consequently, incentivizing the MLO to steer the applicant away from the mortgage solution that is in the consumer’s interest to more profitable terms is generally prohibited, and for good reason.

Relative to presented financing solutions, the law strives to eliminate the lender’s and consumer’s conflict of interest. Any pricing structures or incentives that induce the lender to increase loan-level profits at the direct expense of the consumer are generally prohibited.

What is suggested in the LoanOfficerSchool’s 2022 CE Course is that lenders should seek to evidence appropriate steering by incentivizing MLOs to provide financing that is in the consumer’s interest. Rare and improbable would be a situation where a lender could present evidence that a subprime loan is in the best interest of a consumer who qualifies for prime financing.

The High View of the Mortgage Reforms

Dodd-Frank Title XVI TILA Amendments

(TILA)15 USC §1639b. Residential mortgage loan origination

(c) Prohibition on steering incentives

(3) Regulations

The Bureau shall prescribe regulations to prohibit

- (B) Mortgage originators from steering any consumer from a residential mortgage loan for which the consumer is qualified that is a qualified mortgage to a residential mortgage loan that is not a qualified mortgage

- (C) Abusive or unfair lending practices that promote disparities among consumers of equal credit worthiness but of different race, ethnicity, gender, or age

- (D) Mortgage originators from

- Mischaracterizing the credit history of a consumer or the residential mortgage loans available to a consumer;

- Mischaracterizing or suborning the mischaracterization of the appraised value of the property securing the extension of credit;

- If unable to suggest, offer, or recommend to a consumer a loan that is not more expensive than a loan for which the consumer qualifies, discouraging a consumer from seeking a residential mortgage loan secured by a consumer’s principal dwelling from another mortgage originator.

The CFPB then promulgates the statutory requirements through rule-making, presentations, circulars, and advisory opinions. Let’s review the MLO compensation rules under Regulation Z for those with an appetite for detail. Just what does it mean, and how does one evidence that the lender has acted in the consumer’s interest?

Regulation Z 12 CFR 1026.36 Prohibited acts or practices and certain requirements for credit secured by a dwelling.

§ 1026.36(a)(1)(i) Definitions

“(I) The term “loan originator” means a person who, in expectation of direct or indirect compensation or other monetary gain or for direct or indirect compensation or other monetary gain, performs any of the following activities: takes an application, offers, arranges, assists a consumer in obtaining or applying to obtain, negotiates, or otherwise obtains or makes an extension of consumer credit for another person.”

“The term “loan originator” includes an employee, agent, or contractor of the creditor or loan originator organization if the employee, agent, or contractor meets this definition.”

Comment 36(d)-1 Persons covered

“Section 1026.36(d) prohibits any person (including a creditor) from paying compensation to a loan originator in connection with a covered credit transaction, if the amount of the payment is based on a term of a transaction (the loan amount is generally not a term of a transaction).”

Comment 36(d)-2 Mortgage brokers

“The payments made by a company acting as a mortgage broker to its employees who are loan originators are subject to the section’s prohibitions. For example, a mortgage broker may not pay its employee more for a transaction with a 7 percent interest rate than for a transaction with a 6 percent interest rate.”

Comment 36(d)(1)-2 Section

“1026.36(d)(1) does not prohibit compensating a loan originator differently on different transactions, provided the difference is not based on a term of a transaction or a proxy for a term of a transaction.”

The rule prohibits compensation to a loan originator for a transaction based on, among other things, that transaction’s interest rate, annual percentage rate, collateral type (e.g., condominium, cooperative, detached home, or manufactured housing), or the existence of a prepayment penalty.

Prohibited payments to loan originators § 1026.36(d)(1)

“Comment 36(d)(1)-1.iii Transaction term defined. A “term of a transaction” is any right or obligation of any of the parties to a credit transaction.”

“Compensation may not be based on any term of the transaction or a proxy for any other term of the transaction.”

Comment 36(d)(1)-2.ii Proxies for terms of a transaction

“If the loan originator’s compensation is based in whole or in part on a factor that is a proxy for a term of a transaction, then the loan originator’s compensation is based on a term of a transaction. A factor (that is not itself a term of a transaction) is a proxy for a term of a transaction if the factor consistently varies with a term or terms of the transaction over a significant number of transactions, and the loan originator has the ability, directly or indirectly, to add, drop, or change the factor when originating the transaction. For example:

Example A. Assume a creditor pays a loan originator a higher commission for transactions to be held by the creditor in portfolio than for transactions sold by the creditor into the secondary market. The creditor holds in portfolio only extensions of credit that have a fixed interest rate and a five-year term with a final balloon payment.”

“The creditor sells into the secondary market all other extensions of credit, which typically have a higher fixed interest rate and a 30-year term. Thus, whether an extension of credit is held in portfolio or sold into the secondary market for this creditor consistently varies with the interest rate and whether the credit has a five-year term or a 30-year term (which are terms of the transaction) over a significant number of transactions.”

“The loan originator has the ability to change the factor by, for example, advising the consumer to choose an extension of credit a five-year term. Therefore, under these circumstances, whether or not an extension of credit will be held in portfolio is a proxy for a term of a transaction.”

When are terms not a proxy for a term of the transaction?

“Example B. Assume a loan originator organization pays loan originators higher commissions for transactions secured by property in State A than in State B. For this loan originator organization, over a significant number of transactions, transactions in State B have substantially lower interest rates than transactions in State A. The loan originator, however, does not have any ability to influence whether the transaction is secured by property located in State A or State B. Under these circumstances, the factor that affects compensation (the location of the property) is not a proxy for a term of a transaction.”

If the MLO offers the consumer a subprime loan after the consumer is declined for prime financing, is subprime financing a proxy for a term of a transaction? Probably not. Unless the MLO controls the credit decision, the MLO does not have the ability, directly or indirectly, to add, drop, or change the factor when originating the transaction.

On the other hand, if the MLO controls the credit decision and then consummates a subprime loan, in that case, the MLO may control the factor that serves as a proxy for a term of a transaction.

“Gee, I’m sorry, Mr. Applicant, but you don’t qualify for a prime loan. However, you qualify for our Premier Plus Non-QM program.”

Remember, under Regulation B, when a lender tells a borrower no in relation to a credit inquiry that is an application. A counteroffer is also a credit decision under Regulation B. 12 CFR 1002.2 “Comment 2(f)-3 If in giving information to the consumer the creditor also evaluates information about the consumer, decides to decline the request, and communicates this to the consumer, the creditor has treated the inquiry or prequalification request as an application and must then comply with the notification requirements under § 1002.9. Whether the inquiry or prequalification request becomes an application depends on how the creditor responds to the consumer, not on what the consumer says or asks.”

Inappropriate steering is at the heart of 1026.36(d) prohibitions against compensation based on the loan terms. Therefore, 1026.36(d) and (e) (prohibitions against unlawful steering) are closely related and provide necessary interpretive context.

The need for loan originator compensation rules is related to inappropriate steering and the too-common betrayal of consumer trust. Instead of emphasizing consumer interests, lenders abused the consumer’s dependence on the lender to encourage individual MLOs to engorge themselves in the flesh of vulnerable consumers.

12 CFR §1026.36(e) Prohibition on Steering

§ 1026.36(e)(1) In connection with a consumer credit transaction secured by a dwelling, a loan originator shall not direct or “steer” a consumer to consummate a transaction based on the fact that the originator will receive greater compensation from the creditor in that transaction than in other transactions the originator offered or could have offered to the consumer, unless the consummated transaction is in the consumer’s interest.

Comment 36(e)(1)-1 Steering. For purposes of § 1026.36(e), directing or “steering” a consumer to consummate a particular credit transaction means advising, counseling, or otherwise influencing a consumer to accept that transaction.

Comment 36(e)(1)-2 Prohibited conduct. Under § 1026.36(e)(1), a loan originator may not direct or steer a consumer to consummate a transaction based on the fact that the loan originator would increase the amount of compensation that the loan originator would receive for that transaction compared to other transactions, unless the consummated transaction is in the consumer’s interest.

Comment 36(e)(1)-2.ii Section 1026.36(e)(1) does not require a loan originator to direct a consumer to the transaction that will result in a creditor paying the least amount of compensation to the originator. However, if the loan originator reviews possible loan offers available from a significant number of the creditors with which the originator regularly does business, and the originator directs the consumer to the transaction that will result in the least amount of creditor-paid compensation for the loan originator, the requirements of § 1026.36(e)(1) are deemed to be satisfied.

Remember the thrust of the Title XIV legislation. Lenders should maintain the trust of vulnerable applicants seeking sound advice from mortgage professionals. Folks chasing the American Dream should not become prey to financial predators.

What does all this mean for your loan compensation policy? It means that it is probably a wise idea to invest in written policies and procedures that are appropriately vetted by legal counsel.

Glad we could clear that up for you!

The LOSJ does not provide legal advice. Nor should anything in the LOSJ be construed as a legal opinion on specific facts or circumstances. The contents are intended for general informational purposes only. Readers are encouraged to consult with legal counsel concerning legal matters and specific legal questions.

BEHIND THE SCENES – Keep Your Eyes On the Road

Watch for Rapid Credit Tightening

Fissures Widen in the Residential Mortgage Markets

Institutional Investors Stampeding to Dump CRTs as Recessionary Pressures Loom

“Credit risk transfer – often abbreviated as CRT – is a financial transaction by which the two GSEs shed their responsibility for some of the credit losses on the mortgages they guarantee to institutional investors in exchange for compensation paid to those investors.

In mid-2013, Freddie Mac pioneered the first modern credit risk transfer (CRT) transaction by a GSE; this transferred a portion of the credit risk to private capital sources, thereby reducing the company’s exposure – and the taxpayers supporting it during conservatorship – to that risk. Fannie Mae followed suit later that year. Although many industry observers thought it was just an interesting experiment, such transactions quickly became routine, frequently done, and in large size.

CRT comes into play when the GSEs then enter into a separate financial transaction so that, after the cumulative credit losses on their guarantee of a specific pool of mortgages get to a certain point of severity (called the “attachment point”), the investor reimburses the GSEs for those losses; when those cumulative losses reach some large amount (called the “detachment point”), the CRT investors are no longer responsible for further losses, and the GSEs again will absorb them. Naturally, CRT investors get paid to take this risk: interest rates on CRT instruments are much higher than general mortgage rates, for example, and more akin to interest rates on below-investment-grade bonds.”

– Paraphrase and excerpts from Don Layton, Former FHLMC CEO writing for JCHS Harvard University

“CRT prices have fallen so much that judging by spreads alone, the market looks like it is preparing for a housing crisis as bad as the 2008 recession – Ben Hunsaker, a portfolio manager at Beach Point Capital Management, quoted in the WSJ 10/19/22”

Apart from a brief period at the onset of the COVID pandemic, these risk transference instruments are selling off and pricing near the highest levels since CRTs were introduced a decade ago.

These are uncharted waters. The GSEs reformed their risk management in the wake of the 2008 meltdown. Will these risk transference techniques work in the way intended?

A few indications from the CRT sell-off. Risk mitigation costs money—the greater the perceived risk, the greater the risk transference costs. The market is demanding much greater returns for CRTs. This increase in risk transfer costs means higher mortgage rates on riskier products and/or cessation of types of riskier offerings.

Think about the risk of insuring a driver with a couple of recent DUIs. The GSEs were that driver in 2008. Now, they are drinking again and just bought a Bugatti sports car. Do the capital market’s faith in the GSEs and their untested risk management approaches leave much wiggle room for the road ahead?

The GSEs will have to move soon and move more aggressively to handle declining real estate values and recession uncertainties.

So look for further tightening on credit policy. As risk management costs increase and reduced volume squeezes the GSE’s bottom line, prepare for credit policy changes that attenuate exposure to riskier transactions. For example, appraisal standards will become more stringent, and maximum allowable LTVs may soon decrease in declining markets. Additionally, risk-based loan level add-ons will make some loan types much more expensive.

Tip of the Week – Effective Leadership and Communications Skills are Critical When Presenting Solutions with Esoteric or Riskier Features

With mortgage prospects increasingly gravitating toward riskier loan solutions such as subprime, temporary buydowns, and Hybrid ARMs, communication and leadership skills become increasingly crucial to building trust and rapport.

When the prospect has misgivings about the proposed financing or is confused about the terms, the applicant’s satisfaction with the MLO and lender will suffer. Consequently, aside from failure to close the prospect, the corrosive effects of ham-handed originations can undermine the MLO’s long-term business-building success.

When presenting solutions involving riskier features, begin with a recognizable and well-understood benchmark. Using a 30 or 15-year fixed rate as a benchmark enables the MLO to quantify uncertainties attendant with otherwise esoteric and possibly disconcerting loan features. Everything is relative, and a baseline helps solidify the magnitude of the differences between the presented solutions.

Start with a 30-year fixed-rate loan at one origination point plus zero discounts. Then, illustrate the zero plus zero tradeoff benefit. From there, go back to the one plus zero 30-year fixed rate for the 5/1 ARM comparison. If the seller wants to fund a temporary buydown, illustrate the buydown against the appropriate fixed rate with no temporary buydown.

There should always be at least two illustrations in any loan discussion. Sometimes a third is helpful, sometimes not.

Using this simple baselining technique when comparing terms allows the applicants to grasp the magnitude of the differences between the presented financing, including possible rate changes. Mollify the prospect’s uncertainty surrounding changing payment loans with easily relatable and quantified measures. When successful, the prospect may not like the numbers, which is fine. What the MLO must attenuate is anxiety accompanying unnecessary uncertainty. The prospect can deal with unpleasant numbers. What prospects don’t handle so well is confusion, anxiety, and distrust. They handle that by running and running to someone that does not cause them to feel that way.

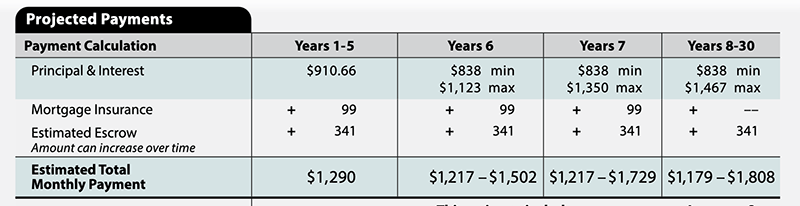

For example, instead of saying, “The interest rate cannot increase by more than 2% per adjustment,” or worse, “the rate can not change much from year to year.” The MLO might better say, “The first payment change could increase your loan payment by approximately $800. For the first 60 months, you’d pay $3995 P&I monthly. Beginning with the 61st month, your P&I payment could increase to $4808 for months 61-72. Then in months 73 -84, to $5662. The P&I payment could not exceed $6547 over the term.” Refrain from contradicting the Loan Estimate’s Projected Payments table. Instead, leverage the Loan Estimate to clarify the presentation. Review the Loan Estimate AIR table. Use the CHARM booklet to reinforce what you are explaining.

Consider showing them an estimated amortization schedule. Then, if they have the capacity, introduce them to concepts of managing the principal balance (amortization acceleration or paying 13 instead of 12 payments every 12 months).

Your client might exclaim, “Whoa, Nellie, that’s a big change. Two years of those payment changes and we’d be in the poor house!” – That is precisely the response you want —a clear objection. However, you will not get manageable objections unless you effectively communicate the magnitude of the uncertainty in understandable and relatable quantified terms. Then, once the MLO brings forth the objection, the MLO can more effectively address the concern.

Facing a clear objection provides a more fitting segue allowing the MLO to better manage the concern by developing sound alternatives. For example, “Mr. Prospect, would you rather choose a loan with no possible P&I changes for the first seven years rather than five?”

The 30-year rate structure is a helpful baseline that allows the applicant to quantify the benefits of other solutions like the 5/1 ARM, 15-year fixed rate, or 2/1 buydown. For example, why should an applicant accept the uncertainty attendant with the 5/1 ARM? “Compared to the 30-year fixed-rate 1 + 0 option, you could save about $18,000 over five years.” “Why would I go with an $1100 higher monthly payment? “Because you then own your house free and clear in just 15 years.”

And remember, DON’T TELL prospects which financing is best when it’s better to SHOW THEM. Create a comparison between the 5/1 ARM and 30-year fixed rate. Explain the risks attendant with the 5/1 ARM and that those risks do not exist with the 30-year fixed rate. Explain the risk of overpaying for the mortgage by selecting the 30-year fixed rate when the 5/1 ARM may be appropriate for their plans. ASK – Which of these structures makes sense for them? Don’t tell them what you would do or why one option is better.

It is infinitely better to help the applicants see the pros and cons themselves. Ask them to tell you how they feel about the magnitude of the potential payment change (quantify the worst-case change for them) in five years. WATCH AND LISTEN to their response. Encourage them to tell you WHY one solution may be better for them. The applicant’s cognition of the differences and advantages between presented options magnifies their buy-in to the selected solution.

Consequently, the applicant’s buy-in improves your customer rapport and credibility. Refrain from imposing your concerns about riskier features on the applicant. State the risks plainly and without fanfare and avoid coming across as an alarmist. Point out that refinancing is never guaranteed and illustrate the risks attendant with a two-step plan (ARM then refi to fixed when possible).

You may alienate the prospect if you are dogmatic about one solution or the other and the applicant does not share your sentiments. For example, suppose you cause the applicant to feel unwise for choosing the riskier features. In that case, that won’t help the applicant, and it certainly does not advance your credibility or rapport with the customer. Instead, they may find a lender that supports their decision and say goodbye to you.