Why Haven’t Loan Officers Been Told These Facts?

The FHFA 41% DTI (Anything over 40.001)

The Journal continues our foray into the byzantine implementation of the FHFA’s ingenious decision to do its part to add to housing cost inflation. As previously reported, angry stakeholders prevailed upon the FHFA to kick the DTI pricing issue down the road for now. Ostensibly to give the little guys a chance to figure out how to navigate this prickly implementation.

Thankfully the GSEs are working hard to level the playing field so the little guys can compete. Can you smell the banks at work? 😉

The LOSJ is not too happy with this implementation. While it is true that someone has to pay for the pricing abatement on low-moderate-income (LMI) loans, is this an appropriate answer? Not being an LMI borrower hardly makes a consumer rich. With housing costs pushing consumer DTI ratios higher and higher, is this the best we can do? This thing may get canceled. Contact your representatives and senators.

The Issue

Should the creditor determine that the DTI exceeds 40.00001% DTI ratio, generally, for loans exceeding 75% LTV, the novel pricing hit is .375. For lower LTVs, the hit is .25. The problem is that once the consumer locks the terms and the MLO presents the Loan Estimate without the DTI hit, subsequently, should the loan manufacture result in a DTI finding over the 40% threshold, what to do with the ensuing pricing hit?

The apparent options are simple. The actual solutions are probably more arcane.

Don’t revise the LE

- Honor the quote. But who pays for the pricing hit (And is that lawful)?

Revise the LE

- Charge the pricing hit to the applicant as a fee

- Build the pricing hit into a higher rate

Perhaps the one question lenders must first answer is determining if adding the DTI hit is a changed circumstance. That may be the crux of the matter.

Additionally, the potential DTI hit begs another question. Can the creditor, the mortgage broker, or the individual MLO absorb the DTI charge, and under what circumstances? The solutions are nuanced and laden with provisos. The answer is YES and NO, and it depends.

Under the compensation rules, a “loan originator” is either an “individual loan originator” or a “loan originator organization.”

“Individual loan originators” are natural persons, such as individuals who perform loan origination activities and work for mortgage brokerage firms or creditors.

“Loan originator organizations” are generally loan originators that are not natural persons, such as mortgage brokerage firms and sole proprietorships.

You are a “loan originator organization” if you are a loan originator that is not a natural person, such as a sole proprietorship, trust, partnership, limited liability partnership, limited partnership, limited liability company, corporation, bank, thrift, finance company, or credit union. (§ 1026.36(a)(1)(iii) and comment 36(a)-1.i.D)

The rules also restrict payments from creditors to their loan originator employees and other “loan originators,” such as mortgage brokers.

§ 1026.36(d) Comment 36(d)-2 Prohibited payments. The payments made by a company acting as a mortgage broker to its employees who are loan originators are subject to the section’s prohibitions. For example, a mortgage broker may not pay its employee more for a transaction with a 7 percent interest rate than for a transaction with a 6 percent interest rate.

When the creditor offers to extend credit with specified terms and conditions, the amount of compensation to the mortgage broker or from the mortgage broker to the individual MLO for that transaction may not change (increase or decrease) based on whether different terms are negotiated.

For example, suppose a creditor agrees to lower the rate initially offered. The new offer may not reduce the mortgage broker’s compensation. Likewise, a mortgage broker may not reduce compensation to an individual MLO based on the new offer.

A creditor or mortgage broker may change credit terms or pricing to match a competitor, to avoid triggering high-cost mortgage provisions, or for other reasons. However, once the loan terms are offered to the consumer, such as when disclosed in the Loan Estimate, the compensation from the creditor to the mortgage broker or from the mortgage broker to the MLO may not change.

Additionally, absent changed circumstances, a mortgage broker cannot reduce compensation if paid directly by the consumer. Comment 36(d)(1)-5 A loan originator organization may not reduce its own compensation in a transaction where the loan originator organization receives compensation directly from the consumer, with or without a corresponding reduction in compensation paid to an individual loan originator.

There is one provision that allows loan originators to take lower compensation. When there are unforeseen increases in settlement costs, the individual MLO may lower the compensation to lower the costs to the consumer within certain limitations.

Specifically, if you are an individual loan originator, you may decrease your compensation to lower the actual settlement cost for a consumer if there is an unforeseen increase in the actual settlement cost over the estimate disclosed to the consumer.

An increase in a settlement cost at closing is unforeseen if the increase occurs even when the estimate provided to the consumer is consistent with the best information reasonably available to the disclosing party when the disclosure was made.

Where have we heard the term “best information reasonably available” before? Here is the million-dollar question. How does one gauge “unforeseen” relative to “best information reasonably available?” That sounds like changed circumstances.

“Best information reasonably available” is the term used in Regulation Z to qualify whether the lender provided specific disclosure in good faith. Changed circumstance describes instances when the best information reasonably available when the lender prepared the disclosure was somehow flawed or insufficient relative to disclosure accuracy.

A revised LE does not constitute a changed circumstance. Instead, the foundation for the changed circumstance is that the lender used the best information reasonably available to prepare the disclosure. Then, subsequently, through no fault of the lender, better information emerged.

Clerical errors or other mistakes are screwups. For example, failing to incorporate standing credit policies into the loan pricing is a screwup, not a change circumstance. Similarly, the failure to calculate the DTI correctly, absent new information, is a screwup, not a change circumstance. The government wants lenders to refrain from making consumers pay for their mistakes.

Don’t give up yet. In the future LOSJ issues, we will visit changed circumstances relative to borrower eligibility and loan originator compensation and try to figure this out!

Do you have a great value proposition you’d like to get in front of thousands of loan officers? Are you looking for talent?

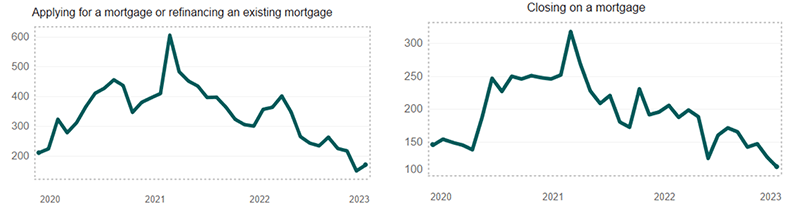

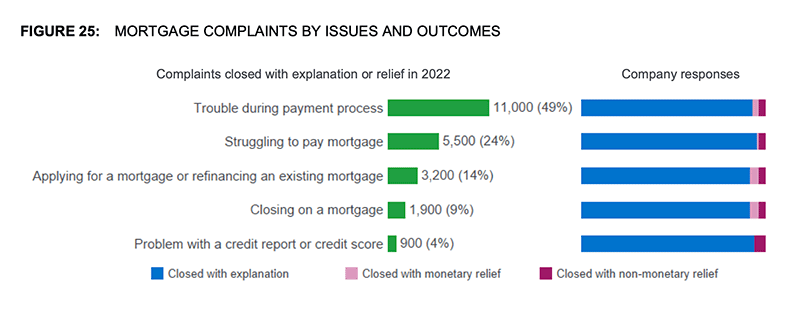

BEHIND THE SCENES – CFPB Mortgage Complaint Numbers Down with Lower Volume

From the CFPB Report

“One area of particular concern to the CFPB is mortgage appraisals. Both undervaluation and overvaluation of a home can hurt both the owners and the surrounding community. In their complaints about purchasing or refinancing a home, consumers generally expressed dissatisfaction with valuations that appraisers provided and described how those valuations frustrated their ability to continue with their purchase. Some consumers stated that they believed they had been discriminated against. In their responses, companies consistently denied any racial bias in their appraisal process or stated that they could not substantiate the consumer’s claims. However, companies did sometimes revisit the original appraisal and raise it after receiving the consumer’s complaint.”

Not so Peachy in Georgia

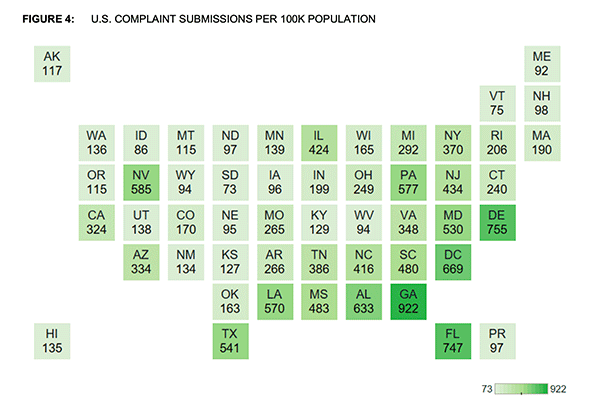

Consumers from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, and other U.S. territories submitted complaints to the CFPB. The CFPB analyzes the geographic distribution of complaints to understand state and regional trends after accounting for population differences. Per capita, the CFPB received more complaints from consumers from Georgia than anywhere else in the United States, followed by consumers in Delaware, Florida, D.C., and Alabama. Consumers in South Dakota submitted the fewest complaints of any state per capita (Figure 4).

Tip of the Week – Sign up for 2023 CE

UDAAP, UDAP, FTC Act Section 5, and Predatory Lending

Are You Confused?

The Loan Officer School will unpack these terms and laws in the 2023 continuing education course.

Do you need clarification on the seemingly hellish cornucopia of statutes and regulations dealing with predatory or abusive lending? For example, what you say to a consumer (or, unfortunately, what they claim you said) may be as important as what you disclose in writing.

How do your loan presentations portray reality? Do you have a well-defined and implemented approach to “act in the consumer’s interest?” Do you know what it means to act in the consumer’s interest?

Interestingly, many federal consumer protection precepts began with the meat packing industry and tobacco company advertising. Join us to discuss the origins and application of the FTC Act (UDAP) and the corollary Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank, Title X UDAAP) in the 2023 CE classes.