Why Haven’t Loan Officers Been Told These Facts?

From the Congressional Budget Office

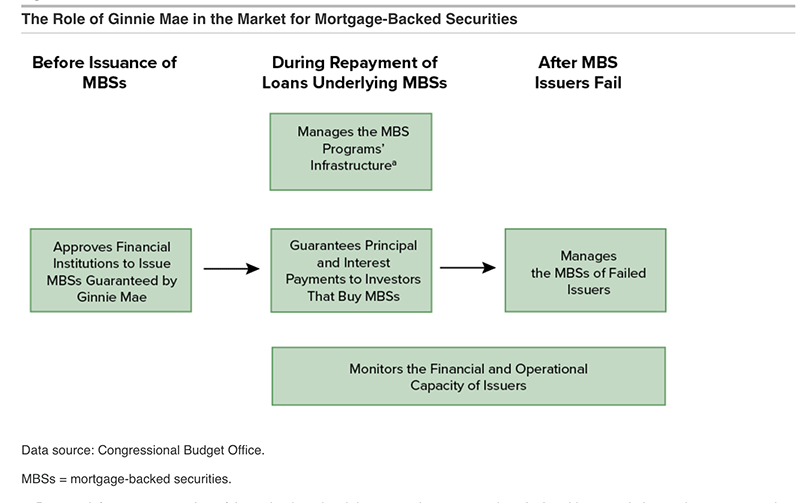

The Government National Mortgage Association, known as Ginnie Mae, is a government-owned corporation within the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Since its establishment in 1968, Ginnie Mae has aimed to attract capital to the market for federally insured mortgages, and thus reduce costs to mortgage borrowers, while minimizing risk to taxpayers. Ginnie Mae carries out that mission by guaranteeing the timely payment of principal and interest on mortgage- backed securities (MBSs) that private financial institutions create from home loans that are insured or guaranteed by other federal programs, such as those of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and the Department of Agriculture’s Rural Housing Service (RHS).

What is GNMA and What Does It Do?

Of all the ways the U.S. Government sponsors homeownership, none is more arcane to the average MLO than GNMA. GNMA is a government agency nested within HUD and is another critical element of government mortgage industry sponsorship.

Generally, government-insured loans are tantamount to high-yield bonds (junk or near-junk bonds). In finance, a higher non-payment risk results in higher yields to the investor and more expensive financing to borrowers. Yet it is different with government-insured loans.

How does someone living paycheck to paycheck with a 625 credit score lacking even a 3.5% down payment get the same or a lower interest rate as the borrower with a 795 score, 25% down, and a 200-month reserve? Apart from the GNMA investor insurance, FHA, VA, and USDA loans would command significantly higher returns.

Because of the GNMA function, people with shaky financials and a higher probability of non-payment obtain the exact pricing as those buyers with a lower risk of non-payment. As is often the case, the pricing of government-insured loans is superior to non-government-insured financing.

Most originators know that FNMA and FHLMC are not that way (Mostly, except for the recent FHFA risk-management lunacy). Even with government sponsorship, FNMA and FHLMC cannot run that way (As will be seen if the federal government continues to foster the housing misadventure). With the two GSEs, as loan level risk increases, so does the pricing for the most part.

Apart from GNMA, the government foreclosure insurance is insufficient risk mitigation to warrant a return on par with other capital market investment grade offerings. Like subprime financing, government-caliber loans would require an easy 150-300 BPS or higher interest rate relative to investment-grade mortgages to attract investors. GNMA attenuates threats to the investors’ return and makes government loans suitable for widespread consumption. Without GNMA’s support, residential real estate would not exist as it is today. Unlike the subprime MBS crisis, GNMA rides shotgun as it did during the apex of the Great Recession.

What Does GNMA Do? See Figure 1.2

GNMA partners with issuers and sponsors to create investments for the capital markets. A sponsor buys up mortgages from lenders, pools them, and packages them for sale to the public, a process known as securitization, which Ginnie Mae, in turn, guarantees. There are a variety of issuers of GNMA-insured MBSs. The issuer or sponsor guarantees payments to investors. That is the first line of defense against US taxpayers having to pay investors in GNMA-insured MBS.

GNMA has requirements for pooled insured loans but doesn’t regulate government foreclosure insurance to lenders. That is the role of FHA, VA, and USDA. Instead, HUD makes the GNMA rules for Sponsors and Issuers of Mortgage Backed Securities comprised of government-insured mortgages. Like the credit policy handbook 4000.1, GNMA publishes a Handbook for MBS issuers pooling government-insured loans as investments.

How Does GNMA Transform Junk Bonds into an Investment Grade Bond? See Figure 1.3 below.

GNMA is like the Fairy Godmother in Cinderella. FHA, VA, and USDA loans are Cinderella loans. Lenders offer government-insured loans to borrowers with scant means and hardscrabble financials. They are unsuitable for princely risk-averse investors (like Wall Street money and capital markets). If these loans went for sale without the GNMA guarantee, Wall Street would demand a high return from these borrowers.

Then comes the credit fairy GNMA. For a fee, the Fairy Godperson (GNMA) waives its magic credit fairy wand (the GNMA Guarantee) over “Loan Pools” (Aggregated groups of individual FHA, VA, and USDA mortgages) of these risky loans.

Instantly, these risky loans transform into princess-grade investment loans, suitable for marriage to the princely investor (capital markets, e.g., Wall Street). GNMA is a wart remover. Uncle Sam adopts these loans as potential liabilities. We tax-payers then back mortgage pool securities with the full faith and credit of the US Government through the Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) structure.

You might own GNMA-insured MBS. If you have money parked in a brokerage account named “Government Insured,” money market, bond, or income fund, chances are you have GNMA-insured MBSs or a mix of U.S. treasury debt and GNMA MBS.

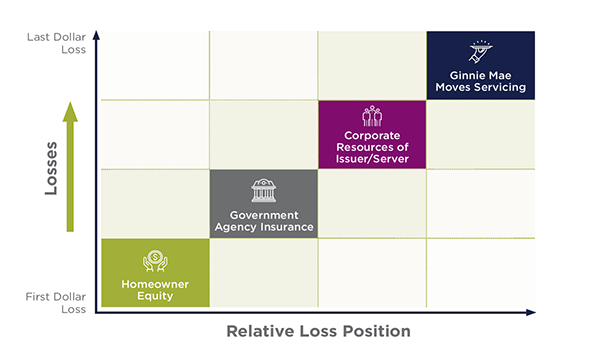

Layered Risk Mitigation, see Figure 1.1

It takes severe mortgage losses to rise to a claim against GNMA-insured MBS. First, properties may have equity to offset losses in foreclosure actions. Next, you have the FHA, VA, and USDA insurance to offset discrete foreclosure losses on pooled loans. Then, if the former mitigations are insufficient, the pool sponsor is on the hook to guarantee payments to investors. Finally, only after these mitigations run dry will GNMA take over the servicing of the pooled loans and start paying investors. Brilliant! Here is another read on how the credit fairy works.

From GNMA

Ginnie Mae’s simple, effective business model exemplifies the power of the Federal Government and the private sector working together. The efficiency of our platform and our single security allows Ginnie Mae to fund the needs and demands of various market segments by leveraging the full faith and credit of the U.S. Government to access global capital.

The Ginnie Mae model significantly limits the taxpayers’ exposure to risk associated with secondary market transactions. Its strategy is to guarantee a simple pass-through security to lenders rather than buy loans and issue its own securities.

Because private lending institutions originate eligible loans, pool them into securities and issue Ginnie Mae mortgage-backed securities (MBS), the corporation’s exposure to risk is limited to the ability and capacity of its MBS Issuer partners to fulfill their obligations to pay investors. By guaranteeing the servicing performance of the Issuer — not the underlying collateral — Ginnie Mae insulates itself from the credit risk of the mortgage loans.

See Figure 1.1

As you can see, Ginnie Mae is in the fourth loss position and is at risk only when all three of the preceding layers of risk protection are exhausted or fail. Additionally, the failure of an Issuer will cause Ginnie Mae to experience financial loss only to the extent that funds are needed to transfer the servicing to another Issuer or to the extent there is deterioration in servicing value.

Ginnie Mae monitors the delinquencies in Issuer servicing portfolios in an efficient and effective manner to mitigate the potential losses associated with Issuer defaults.

Do you have a great value proposition you’d like to get in front of thousands of loan officers? Are you looking for talent?

BEHIND THE SCENES – CFPB Announces Revised Methodology for Determining Average Prime Offer Rates

(APOR is used in Regulations Z and C as a baseline for several sections, including, High-Cost loans, Higher-Priced-Mortgage loans, and QM loans)

WASHINGTON, D.C. – Today, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) announced a revised version of its “Methodology for Determining Average Prime Offer Rates.” The revised methodology describes the calculations used to determine average prime offer rates (APOR) for purposes of federal mortgage rules. APORs are annual percentage rates derived from average interest rates, points, and other loan pricing terms currently offered to consumers by a representative sample of creditors for mortgage loans that have low-risk pricing characteristics.

The methodology statement has been revised to address the imminent unavailability of certain data the CFPB previously relied on to calculate APORs, as a result of a recent decision by Freddie Mac to make changes to its Primary Mortgage Market Survey® (PMMS). The CFPB has identified a suitable temporary alternative source of the relevant data and will begin relying on those data to calculate APORs on or after April 21, 2023.

On or after April 21, 2023, the CFPB will begin using ICE Mortgage Technology data and the CFPB’s revised methodology to calculate APORs.

The CFPB will continue to post the survey data used to calculate APORs on the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council’s website, and the CFPB will continue to identify the source of the data on that page.

The calculation of average prime offer rates (APORs) is based on survey data for eight mortgage products (the eight products): (1) 30-year fixed-rate; (2) 20-year fixed-rate; (3) 15-year fixed-rate; (4) 10-year fixed-rate; (5) 10/6 variable rate; (6) 7/6 variable rate; (7) 5/6 variable rate; and (8) 3/6 variable rate. The survey data includes data for “best quality,” 80 percent or less loan-to-value, first-lien loans. All four variable-rate products adjust to an index based on the 30-day Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) plus a margin and adjust every six months after the initial, fixed-rate period. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) makes available the survey data used to calculate APORs.

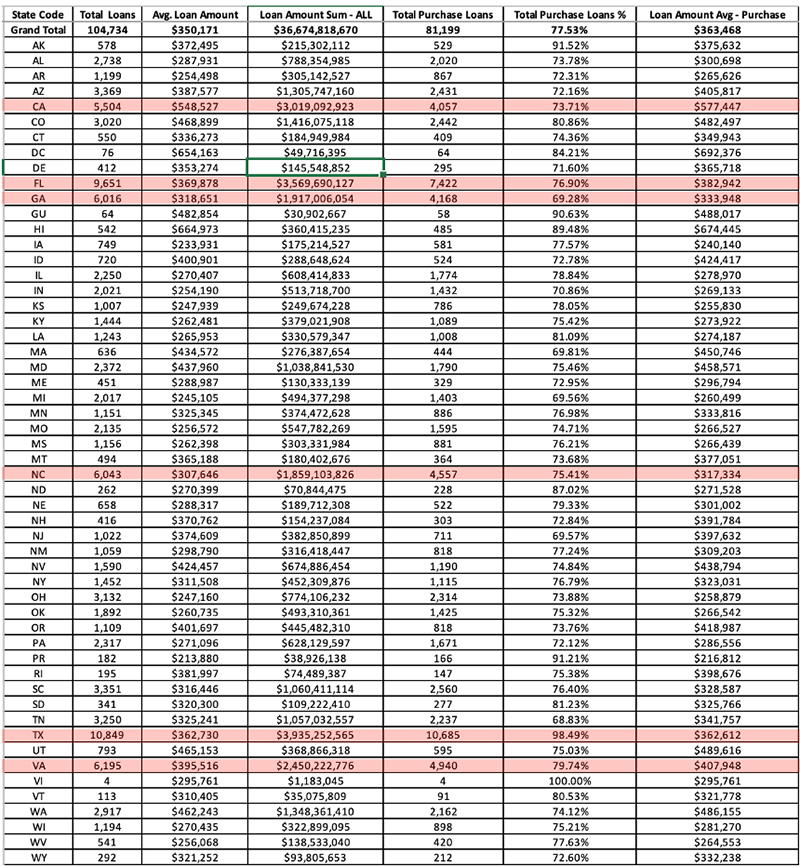

Tip of the Week – Check the Data – VA, Interesting Numbers

Got Texas VA Loan Product? Fiscal 2023 Q1 (October 1 – December 31, 2022) VA Loan Volume

Twice as many units closed in Texas compared to California in the last quarter of 2022. Note the percentage of purchase units in the great state of Texas. Five other states are outdoing the Golden State’s VA loan production.

No surprise that Florida is also putting up significant numbers.