Why Haven’t Loan Officers Been Told These Facts?

FNMA Community Seconds® – Better Than Sliced Bread

Years ago, the piggyback mortgage origination was a staple solution before novel GSE pricing adjustments ruined secondary financing as a viable alternative to PMI.

The piggyback’s primary benefit was the ability to defeat the necessity for PMI or reduce the PMI cost. In addition to lowering the financing costs, the piggyback structure allowed for greater underwriting flexibility in that what is possible at an 80% LTV is not at 95%. But that ended when the GSEs began charging ballistic pricing hits for transactions with secondary financing.

The piggyback has enjoyed a possible resurgence. Last year, the GSEs announced the waiver of credit fees in connection with low-moderate-income lending, including transactions with

secondary financing (Loans to first-time homebuyers with qualifying income ≤100% of area median income (AMI) or 120% AMI in high-cost areas).

But what about the households that exceed the income cutoffs for credit fee waivers? Or what if the transaction does not meet the first-time buyer definition?

What program permits 105% CLTV (No High-Balance first mortgages) with no MI (80% LTV), no first-time buyer requirement, no AMI requirement, no minimum borrower contribution requirement, no manufactured home prohibition (CLTV > 95% MH Advantage only), and no loan-level pricing adjustments for secondary financing? Why the FNMA Community Seconds® program, of course.

The FHLMC has similar policies for their Affordable Seconds® program.

Here is how it works. The FNMA or FHLMC provides the primary financing, which includes the 5/6mo hybrid ARM or fixed-rate mortgage products. Of course, the secondary financing must come from allowable types of sources and otherwise meet specific loan parameters to qualify for the Community Second program.

The GSEs do not facilitate the secondary financing. Instead, FNMA accommodates the borrower’s use of secondary financing without pricing hits to the primary financing when the second meets the Community Seconds requirements.

The waiver of the pricing adjustments for secondary financing is no insignificant perk. FNMA LLPAs range between 1.125 to 1.875 to the price.

Unlike the duty to serve and low-moderate-income programs, the Community Seconds/Affordable Seconds have no means or income tests. Yes, this is truly an egalitarian solution for both rich and poor borrowers.

Note that a permissible source of secondary financing is the borrower’s employer. Do employers do such things? Indeed, do black bears shhhhhimmmy up trees? For high-potential employees, among other benefits, employer-provided housing benefits may include secondary financing. Employers provide secondary financing to enhance an employee’s relocation, retention, or recruitment. The days of ultra-cheap money might be gone, but money is still relatively cheap.

Example A: $900,000 sales price. $720,000 first mortgage. The employer provides a second mortgage of $90,000 for 15 years, and the borrower puts 10% down. The employer loan requires no payments until the home is sold or the end of the term.

Example B: $900,000 sales price. $720,000 first mortgage. The employer provides a $198,000 second mortgage, with a 15-year term for a CLTV of 102%. The employer defers interest and payments for three years before changing to fully amortizing, equal monthly payments based on the first mortgage rate. The employer forgives the remaining loan after five years of employment.

For single-family, FNMA permits 80% or higher LTV and requires no minimum borrower contribution. 2-4 units exceeding 80% LTV require a 5% borrower contribution.

FNMA: Permissible secondary financing from the following sources

Community Seconds funds are provided by any one of the following, so long as it is not the property seller or other interested party:

- A federal agency, state, county, or similar political subdivision of a state.

- A self-governing city, town, village, or borough of a state.

- A housing finance agency (HFA).

- A nonprofit organization exempt from taxation under Section 501(c)(3)of the Internal Revenue Code.

- A regional Federal Home Loan Bank under one of its affordable housing programs.

- A federally recognized Native American tribe or its Tribally Designated Housing Entity(TDHE).

- An employer, where the borrower is an employee.

- A lender only in connection with an employer-guaranteed Community Seconds loan as part of its affordable housing program.

When the borrower’s employer is the provider of the Community Seconds loan, the financing terms may provide for the employer to require full repayment of the debt if the borrower’s employment is terminated (either voluntarily or involuntarily, for reasons other than those related to disability) before the maturity date of the Community Seconds loan.

As they say, the devil is in the details. The secondary financing cannot exceed the primary note rate by over 2%. The maturity date of the Community Seconds loan, or the due date of any balloon payment on the Community Seconds loan, cannot be before the earlier of:

- 15 years after the note date of the first mortgage or

- The maturity date of the first mortgage.

See the FNMA and FHLMC program checklists at the links below. Carefully review the seller guide.

FNMA Community Seconds® Checklist

FHLMC Affordable Seconds® Checklist

Do you have a great value proposition you’d like to get in front of thousands of loan officers? Are you looking for talent?

BEHIND THE SCENES – FNMA Report Underscores Mortgage Industry Focus on Larger Loans to the Detriment of Low-Moderate Income Households

A recent report by FNMA on the economics of low-balance loans provides a broad view into technical elements of mortgage profits. The report’s thrust is mortgage economics related to lower loan balance lending. However, the report also reveals some hard truths about mortgage origination practices.

The report, published in December 2023, identifies what is evident to most lenders: on the whole, when lenders are busy, lenders focus on larger, more profitable loans. When lenders have spare time, they minister to the needs of the underserved – those consumers who are over-represented in the consumption of relatively lower-balance mortgages.

Individual loan officers make mortgage profits much like origination organizations, by volume. Lender’s margins improve with higher efficiencies, including lower costs per loan. Lenders comprehend manufacturing costs as a percentage of the loan volume or cost per unit. In either measure, the greater the volume and the lower the number of units, the higher the efficiency and profits.

Fair Lending Ramifications

The ECOA and FHA do not specifically enumerate low-or moderate-income borrowers as protected persons. However, owing to the pervasive wealth gap between people of color and white folks, higher-balance loans are consumed disproportionately by whites, and lower-balance loans are over-represented by people of color. Therefore, pursuing more profitable higher-balance loans in a volume-constrained environment often comes at the expense of persons consuming lower-balance loans, leading to disparate impacts along protected-class lines.

The term “disparate impact” is a legal precept the US Supreme Court has upheld.

From the FFIEC Interagency Fair Lending Examination Procedures:

- The courts have recognized three methods of proof of lending discrimination under the ECOA and the FHAct:

- Overt evidence of disparate treatment

- Comparative evidence of disparate treatment

- Evidence of disparate impact

Disparate Impact

When a lender applies a racially or otherwise neutral policy or practice equally to all credit applicants, but the policy or practice is disproportionately excludes or burdens certain persons on a prohibited basis, the policy or practice is described as having a “disparate impact.”

Example: A lender’s policy is not to extend loans for single family residences for less than $60,000.00. This policy has been in effect for ten years. This minimum loan amount policy is shown to disproportionately exclude potential minority applicants from consideration because of their income levels or the value of the houses in the areas in which they live.

The fact that a policy or practice creates a disparity on a prohibited basis is not alone proof of a violation. When an Agency finds that a lender’s policy or practice has a disparate impact, the next step is to seek to determine whether the policy or practice is justified by “business necessity.” The justification must be manifest and may not be hypothetical or speculative. Factors that may be relevant to the justification could include cost and profitability. Even if a policy or practice that has a disparate impact on a prohibited basis can be justified by business necessity, it still may be found to be in violation if an alternative policy or practice could serve the same purpose with less discriminatory effect.

Finally, evidence of discriminatory intent is not necessary to establish that a lender’s adoption or implementation of a policy or practice that has a disparate impact is in violation of the FHAct or ECOA.

The ECOA and FHA

From the FNMA Report

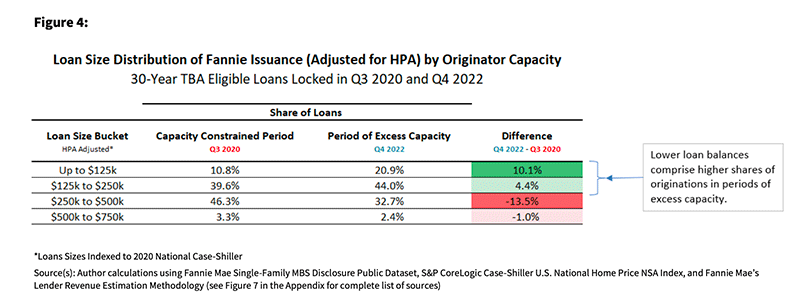

“Originators tend to originate a relatively higher share of higher balance loans in capacity-constrained environments [busy periods] compared to during periods of excess capacity [such as late 2023]. Such loans tend to be made to higher-income borrowers who face fewer barriers to obtaining mortgage credit. This might suggest that there is a greater likelihood of originators focusing on lower-balance lending when they have surplus capacity [when I have the time], such as when mortgage rates increase dramatically, as seen in recent months.”

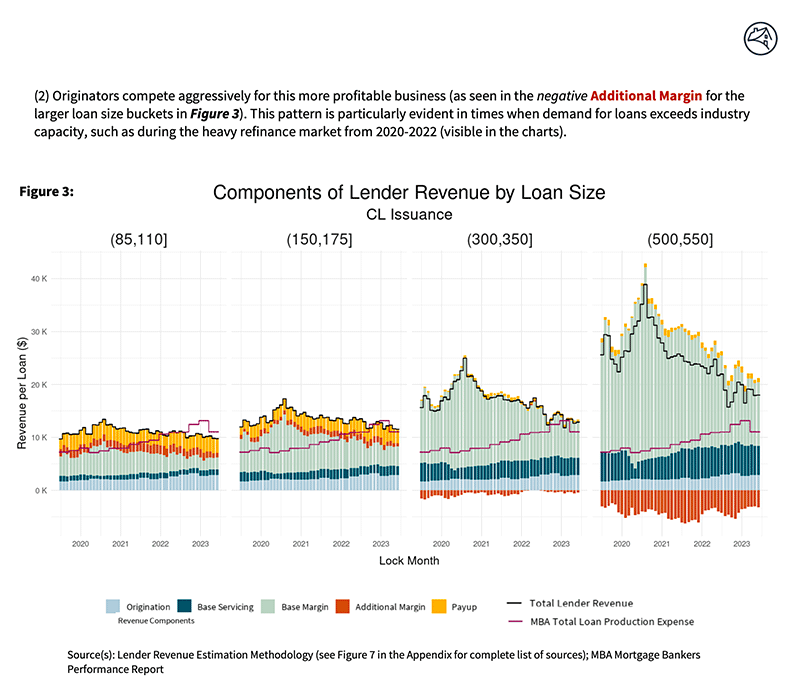

The report is quite technical, but the data and analysis aim to redefine the profitability measures of making lower balance loans by integrating “Specification PayUp, a.k.a. Spec PayUp” benefits into the economic analysis.

Spec PayUps (From the Report)

In mortgage pools and whole loan delivery, the GSEs may offer premiums for loans with a relatively lower likelihood of early prepayment. When rates fall, prepayment (payoff before maturity) introduces the investor to interest rate risk. Loan balance is one criterion. The term “lower balance” generally applies to conforming loans under $250,000 but will vary based on the capital markets. When rates fall, and the investor holds onto their higher-yielding mortgages, the value of the investment improves.

The benefit of investing in lower-balance loans is the diminished prepayment and rate risk compared to higher-balance loans. In other words, if a pool of loans is at 6.50%, then for the investor, should rates drop under 6.50, you are more likely to hold onto the higher-yielding mortgages if investing in lower-balance loans.

Why Ignore Low Balance Lending?

The report’s discussion of payups is fascinating, but perhaps of greater importance is that the data supports a hypothesis that a low-balance lending market develops during busier periods, which is no secret to the MLO on the street. The appetite for less profitable loans increases every time mortgage activity dips. Why not find a way to make low-balance lending economically viable for providers?

However, the disturbing conclusion from the data is the apparent ongoing stratification of mortgage consumers. The economics of low-balance lending leads to a “second-class” of borrowers with second-class credit opportunities. In relation to fair lending laws, the fact that low-balance loans are over-represented by people of color is of particular concern. Due to mortgage economics, an entrenched two-tier credit opportunity system persists despite so many fair lending efforts. If it were not for spec payups, equal access to credit would be further diminished for low-moderate-income borrowers.

No Easy Fixes, Yet More Can Be Done

Spec payups are a function of equitable return on investment. More positive steps might also make a difference. For starters, single-family tax-free MBS securities comprised of low-balance loans would be an excellent start. These structures already exist for targeted communities. Additionally, incentivizing MLOs to target communities for outreach with subsidized financing programs would make a difference.

There are no boil-the-ocean solutions to the persistent wealth gap challenge. However, homeownership is a crucial element of necessary holistic improvements to close the gap. Many small steps may add up to big improvements.

FNMA’s Report on Low Balance Lending Economics

Graphics courtesy of the FHFA and FNMA

Tip of the Week – Loan Presentations Require Contrast

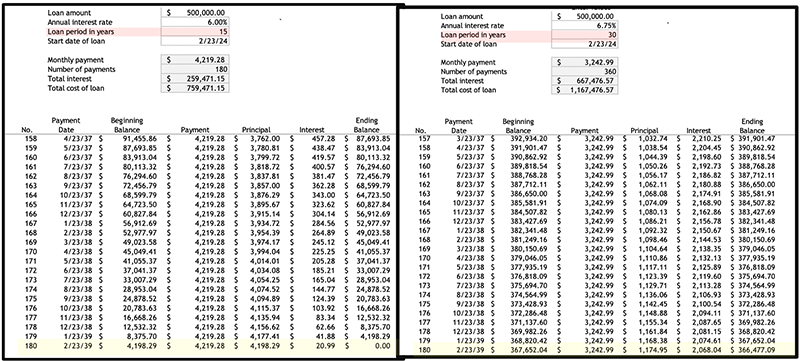

With all loan presentations, always provide the applicant with something to compare. In most cases, there is no better baseline than the 30-year fixed-rate loan.

Most consumers identify loans with changing payments as presenting a risk of overpaying for the mortgage or unaffordable outcomes. The 30-year fixed rate provides a baseline to measure the benefits of competing solutions such as an ARM or a 15-year term.

When presenting the 15-year solution to the applicant, the applicant objected that the P & I was “too high.” The applicant further stated the payment would “hinder their financial flexibility and options.”

However, is the applicant comprehending their “financial flexibility and options” apart from a more global side-by-side comparison? The P & I analysis concludes that the 15-year term “costs” $976 more per month. Hence, in the eyes of the applicant, the loan is unaffordable. On the other hand, run an amortization table on both loans and illustrate the 30-year loan balance at the end of 15 years.

Mr. Applicant, 15 years from now, would a mortgage-free home improve your financial options and flexibility more than having 15 more years of $3243 payments?

That is a stark and well-quantified benefit only made possible through comparison.

Another example is the five-year hybrid ARM. In this comparison, juxtapose the principal and interest payments of the fixed rate and the ARM. In addition to the lower P&I payments, for those applicants who intend to payoff the ARM during the initial rate period, the ending loan balance at the end of the initial rate period will be lower on the ARM due to the rate differential impact on amortization.

Most stakeholders regard the 30-year fixed-rate loan as the least risky mortgage solution. Don’t debate that conclusion. Instead, work with it and let the comparative analysis be their teacher.

In addition to providing quantified benefits in the mortgage comparisons, the lender has evidence that the borrower made an informed decision when selecting a mortgage other than a 30-year fixed-rate option. Suppose someone should challenge that the lender acted in the consumer’s interest. In that case, the lender may be in a more defensible position with evidence of appropriate loan comparisons.